Description

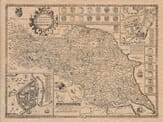

John Speed added a short essay which would have been published on the rear (the verso) of this old map of Yorkshire which we have translated into modern English. It should be noted that some errors may have occurred within the translation.

As the courses and confluences of great rivers are mostly fresh in memory, even though their sources and fountains are often unknown, so too are the later understandings of great regions not forgotten, despite the obscurity of their origins due to the passage of time and the many changes that have occurred. In describing the great region of Yorkshire, I will not focus on matters close to us, but briefly mention those that are more distant. However, I won’t do this in a way that diminishes the dignity of such a notable country, nor so extensively as to waste time praising something that has never been criticized. Although it might seem unnecessary to recount ancient memories about the name and nature of this nation, especially considering the changes in time itself (which brings different effects in every age) and the way people often take less pleasure in the past than in discussing current events, I still think it is appropriate to start from where the first clear direction is given. Even ancient matters can be useful, either by imitation or comparison, and repeating them will not be irrelevant.

You should understand that the County of York, in the Saxon language, was called Euepnic-rcype, Effnoc-rcyne, and Ebona-rcype, and is now commonly called Yorkshire, a region much larger and with more miles in its borders than any other county in England. It owes much to the loving care of Nature, which placed it in such a temperate climate, so that it is equally fruitful in every measure. If one part is rocky and sandy, barren land, another part is fertile and richly adorned with cornfields. If you find one place bare and lacking in woods, another is shaded by forests full of large trees, producing many fruitful and profitable branches. If one area is marshy, muddy, and unpleasant, another offers a delightful view, full of beauty and variety.

To the north, the Bishopric of Durham borders it, separated by the River Tees. The German Sea lies to the east, lashing the shores with its tumultuous waves. The west is bordered by Lancashire and Westmorland. To the south, it is enclosed by Cheshire and Derbyshire (friendly neighbors), and then by Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire; the famous Humber estuary divides it, into which all the rivers that water this land empty themselves, offering their regular tribute, as if into the common storehouse of Neptune, holding the watery assets of this province.

This whole county, being so vast, is divided into three parts for easier and more effective governance: these are called The West Riding, The East Riding, and The North Riding. The West Riding is bordered by the River Ouse, Lancashire, and the southern boundary of the county, and faces the west and south. The East Riding curves toward the ocean, bounded by the River Derwent, and faces the part where the sun rises, brightening the world with its beams. The North Riding extends northward, bordered by the River Tees, Derwent, and a long stretch of the River Ouse. The county spans nearly 70 miles from south to north, from Hart-hill to the mouth of the Tees. Its breadth from Flamborough Head to Horncastle on the River Lune is 80 miles, with a total circumference of 308 miles.

The soil of this county is generally fertile and yields enough crops and cattle. One area is particularly known for its quarries, where freshly cut stones are soft, but naturally harden over time with exposure to wind and weather. Another area is noted for a type of limestone, which, when burned and transported to other, colder, hillier parts of the county, serves to fertilize and enrich the fields.

The Romans, flourishing in military prowess, made many settlements here, as shown by their monuments, inscriptions found in church walls, Roman-style columns discovered in churchyards, and votive altars dug up, presumably erected to their local gods, who were considered the guardians of specific places. The Romans also left behind bricks, which they used in times of peace to keep their legions active. These bricks, found over time and bearing Roman inscriptions, prove the ancient presence of the Romans in the area.

The many monasteries, abbeys, and religious houses established in this county are also a sign of its piety. While these buildings once added great beauty and grandeur, since their dissolution and the ravages of time, they have become mere ruins, leaving only remnants to show their former splendor. Examples include the Abbey of Whitby, founded by Lady Hilda, the Abbey of Bolton (now razed), Kirkstall Abbey (founded in 1147), the Abbey of St. Mary in York (later converted into a manor), the Abbey of Fountains (founded by Archbishop Thurstan of York), and many others, such as those built by King William the Conqueror at Selby in memory of Saint German. These religious establishments attracted pilgrims and became renowned for their holy purposes, though with time, they have been subject to decay, now serving as historical monuments to the past.

Many places in this province are famous not only for their name but also for their fortunate location or other lucky circumstances. Halifax is known for being the birthplace of Johannes de Sacro Bosco, the author of the “Sphere.” It is also famous for its law against stealing and for the size of its parish, which includes eleven chapels and a population of twelve thousand people. In the past, it was called Horton, and there is a curious story about the change of name: a clerk, deeply in love with a maiden, unable to win her affection through praise or promises, turned his love into rage and beheaded her. Her head was later hung on a yew tree, and it became a revered relic until it decayed. People continued to visit, believing it to be a holy object, and it maintained a reputation for reverence and religion, even becoming a place for pilgrimages.