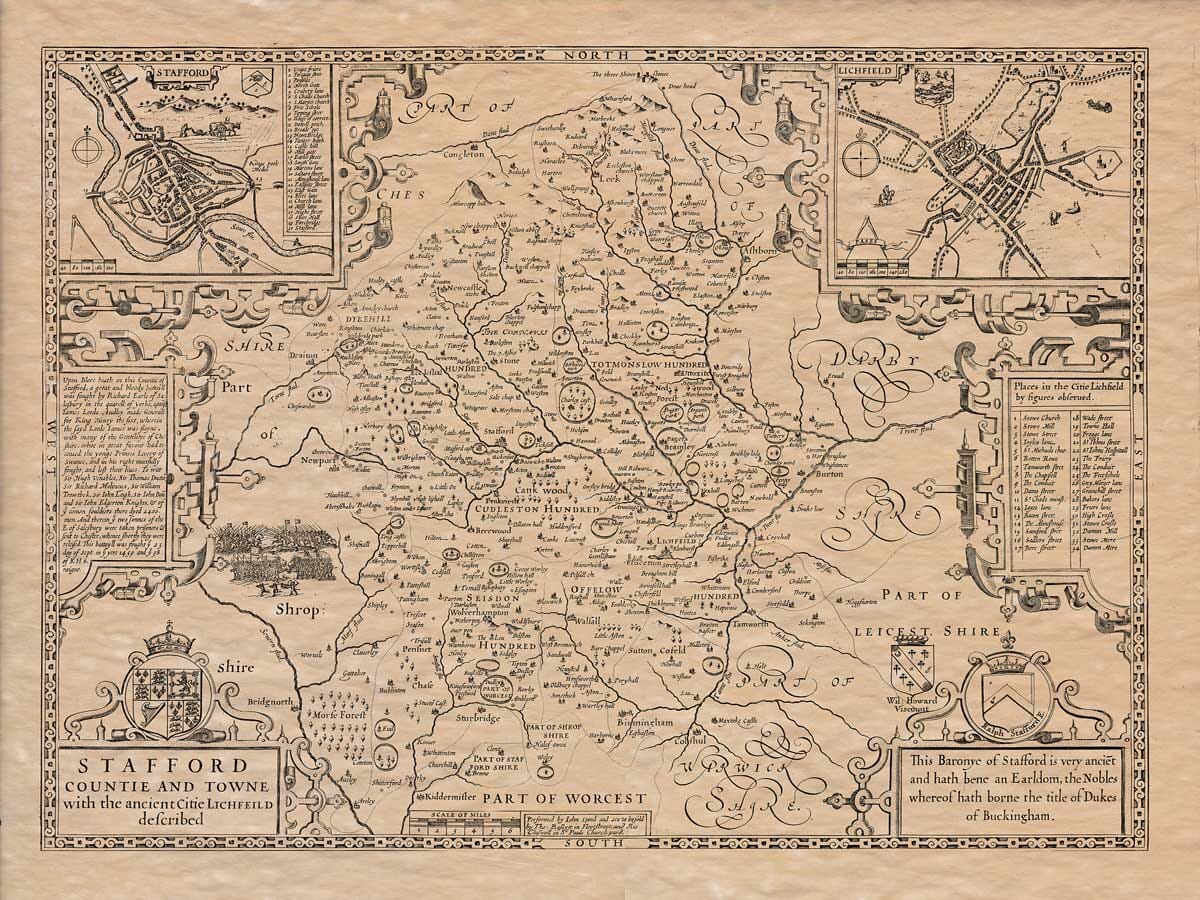

Description

John Speed added a short essay on the county which was published on the rear (the verso) of

the map which we have translated into modern English . . .

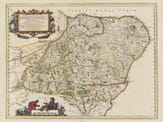

Staffordshire, which in Old English is written Staffons-rcyne, is located roughly in the center of England. To the north, it borders Cheshire and Derbyshire, meeting at a point where three boundary stones mark the junction of the counties. It is separated from Derbyshire to the east by the rivers Dove and Trent; to the south, it borders Warwickshire and Worcestershire; and to the west, it adjoins Shropshire.

The shape of the county is somewhat like a diamond—narrow at both ends and widest in the middle. It stretches 44 miles from north to south and is 27 miles wide from east to west, with a total perimeter of 140 miles.

The air is clean and very healthy, though rather sharp and cold in the northern moorlands, where snow tends to linger and the winds are biting.

The soil in the northern part is poor for growing crops, as the hills and moors are unsuitable for farming. The central area is flatter but heavily wooded—evidenced by the large forest called Cannock. The southern part is the most fertile, producing abundant grain and good pastureland.

The original inhabitants were the Cornavii, whom the ancient geographer Ptolemy placed in the region covering what is now Shropshire, Worcestershire, Cheshire, and Staffordshire. These lands were later part of the Mercian Saxon kingdom during the time of the Heptarchy, with Tamworth in Staffordshire serving as the royal court. The Danes also attempted to settle here, as shown by the place name Tettenhall (formerly Theoten Hall, meaning “hall of the heathens”), which was the site of a bloody battle won by King Edward the Elder. The Venerable Bede referred to the people of this area as “the Midland English,” as he believed it lay in the heart of the country. After the Norman Conquest, many Normans settled here, and their descendants have since spread to other regions.

The county’s main resources include grain, livestock, alabaster, timber, and iron—though ironworking may deplete the forests. There are also coal deposits, and the land produces ample meat and fish. The River Trent, known for its abundance of fish, along with other rivers like the Dove, Manifold, Churnet, Hamps, Tame, Tean, Blithe, Tyne, and Sow, enrich the land so much that the meadows remain green even in winter. The Trent is the most important of these and is considered the third-greatest river in England.

The county town, Stafford, was once called Betheney, named after a holy man, Bertelin, who lived there as a hermit. King Edward the Elder built the town; it was later incorporated by King John. The town was fortified on the east and south by walls and ditches built by local barons, while the north and west were protected by a large pool, now converted into meadowland. The circuit of the walls was 1,240 paces long, with four gates facing the cardinal directions. The River Sow flows along the south and west sides. King Edward VI granted the burgesses (citizens) a permanent governing body. The town is run by two annually elected bailiffs, chosen from a council of 21 assistants called the Common Council, along with a recorder (an office once held by the Dukes of Buckingham), a town clerk (from whom this information was gathered), and two sergeants-at-mace to assist them. The town lies at latitude 53°20′ and longitude 18°40′.

Lichfield, though not the county town, is larger and more famous, and also much older. It was known to Bede as Licidfield, interpreted by Rous as “the field of the dead” due to many saints martyred there during the persecution by Emperor Diocletian. The city’s coat of arms reflects this, showing a landscape with various saints being martyred. King Oswy of Northumbria built a church there after defeating the pagan Mercians and established it as the seat of Bishop Diuma. Later bishops became wealthy and persuaded King Offa—and through him, Pope Adrian—to elevate Lichfield to an archbishopric, much to the dismay of the Archbishop of Canterbury. The church became the resting place of Mercian kings Wulfhere and Ceolred. In the age of grand architecture, Bishop Roger Clinton rebuilt the old cathedral, dedicating it to the Virgin Mary and St. Chad, while Bishop Langton enclosed the cathedral close with walls. The city is governed by two bailiffs and one sheriff, elected annually from among 24 burgesses, with a recorder, town clerk, and two sergeants to assist.

Religious houses were established throughout Staffordshire in places like Lichfield, Stafford, De la Crosse, Croxden, Trentham, Burton, Tamworth, and Wolverhampton. These religious institutions, having grown wealthy and proud, lost sight of their founders’ intentions and attracted criticism. Eventually, under King Henry VIII, they were dissolved, and their wealth was redirected to help the poor and fund schools—acts considered more charitable and useful to the country.

The county once contained 13 castles and has 19 market towns for trade. It is divided into five hundreds (administrative districts), which together contain 130 parish churches, listed in alphabetical order in the table.