Description

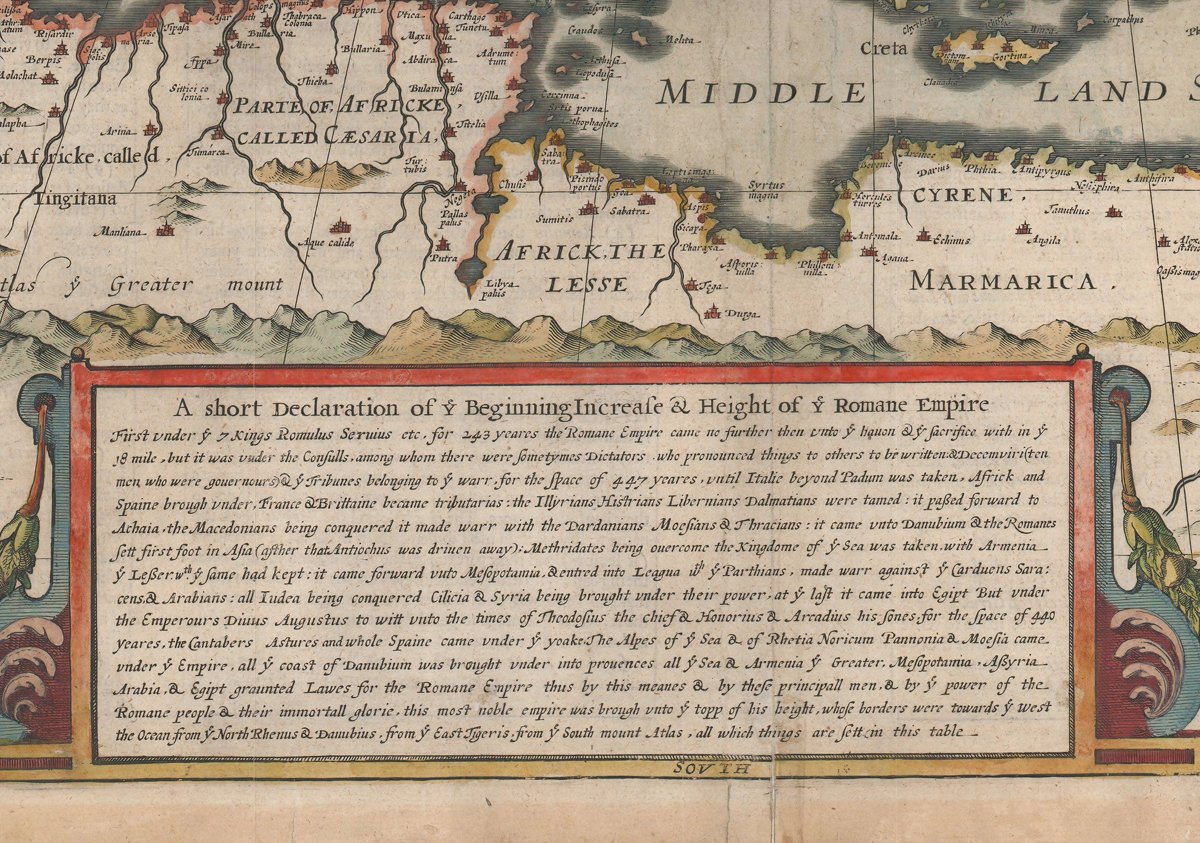

Here we’ve translated John Speed’s description featured on the map into modern English:

A Brief Declaration of the Rise and Expansion of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire, under its kings, starting with Romulus and Servius, lasted for 243 years. During this time, the empire did not extend beyond the limits of the city of Rome, which was about 18 miles in all directions. However, under the consuls—who were occasionally joined by dictators, men appointed to act as rulers—and the Decemvirs (a group of ten governors), as well as military tribunes, the empire expanded over 447 years. It grew from Italy, beyond the Po River, to include Africa and Spain. France and Britain became tributary states. The Illyrians, Histrians, Liburnians, and Dalmatians were subdued.

The empire expanded into Greece, where Macedonia was conquered, and war was waged with the Dardanians, Moesians, and Thracians. The Romans crossed the Danube River and first set foot in Asia after Antiochus was defeated. After overcoming Mithridates, the Kingdom of Pontus and Lesser Armenia were added to the empire. It continued to advance into Mesopotamia, and the Parthians were eventually defeated. Wars were fought against the Carduans, the Saracens, and Arabians. Judea was conquered, and both Cilicia and Syria were brought under Roman control.

Eventually, the empire reached Egypt. Under the emperors, beginning with Augustus and continuing through to the reigns of Theodosius, Honorius, and Arcadius (a period of 440 years), the Cantabrians, Asturians, and all of Spain came under Roman rule. The Alps, the lands of the Sea (likely meaning the coastlines), Rhetia, Noricum, Pannonia, and Moesia were all incorporated into the empire. All the lands along the Danube River were brought into the empire as provinces. The entire Mediterranean coastline, Greater Armenia, Mesopotamia, Assyria, Arabia, and Egypt came under Roman dominion.

Through the efforts of these great leaders and the power of the Roman people, the empire reached the height of its glory. Its borders stretched from the West, where it met the Ocean, to the North, along the Rhine and Danube Rivers, to the East, reaching the Tigris River, and to the South, where the borders met Mount Atlas. All of this is shown in the accompanying map.

Furthermore the maps within John Speed’s atlas of 1627 contained further notes on the rear (the verso) of each map. Here we’ve made a further attempt to translate the fascinating script to into modern day English.

The Roman Empire by John Speed Verso

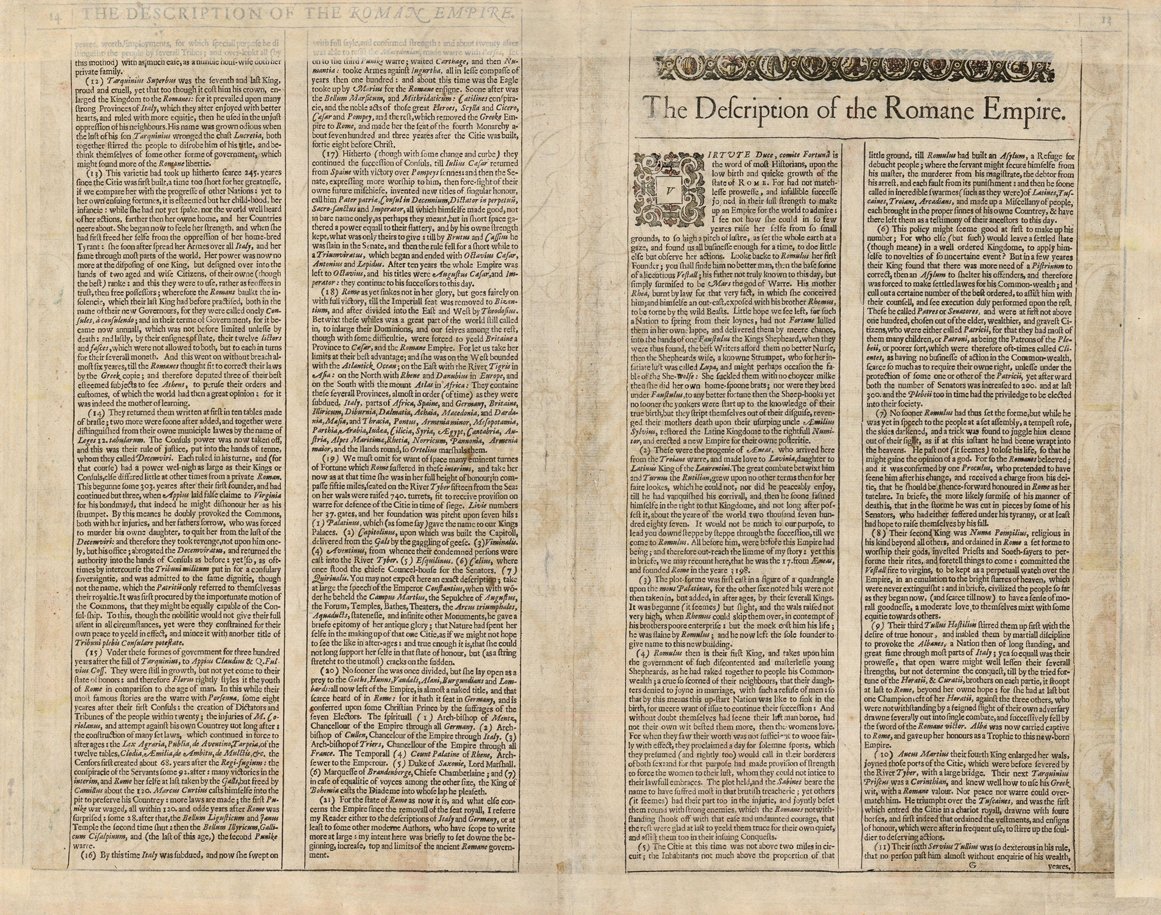

The Description of the Roman Empire

Virtue in Leadership, Fortune in Fate: These are the words most historians use to describe the humble beginnings and rapid rise of the state of Rome. Without extraordinary valor and the favor of Fortune, it’s hard to imagine how the Roman Empire could have emerged so quickly and powerfully, to the point where it captured the attention of the entire world. In such a short time, this small and seemingly insignificant city grew into a mighty empire, becoming the center of attention for all of humanity.

Look back to Romulus, the first founder of Rome. He was no extraordinary man; in fact, he was the illegitimate son of a Vestal Virgin, Rhea Silvia. His father, though never truly identified, was believed to be Mars, the god of war. His mother was condemned to death by the law for the crime of bearing him. Romulus and his twin brother, Remus, were cast out and left to die in the wild, exposed to the elements. Yet, by the hand of fate, they were discovered and cared for by the shepherd Faustulus, who raised them. Their nurse was a woman of ill repute, known as Lupa, who was possibly the source of the famous myth of the she-wolf. Despite their lowly beginnings, once they learned their true heritage, they cast off their disguise, avenged their mother’s death, and ousted their usurping uncle, Amulius, restoring the kingdom to its rightful heirs.

Romulus and Remus were descendants of Aeneas, the Trojan hero, who had fled the burning city of Troy and eventually married Lavinia, daughter of the Latin king of the Laurentians. Aeneas’ battle with Turnus, the Rutulian prince, was fought over Lavinia’s beauty. Once he defeated Turnus, Aeneas took control of the kingdom, which he established around 2787 years after the foundation of the world. Although there were many rulers before Romulus, they were part of a different era, before the rise of Rome, and their stories fall outside the scope of this account. In brief, Romulus was the 17th in line from Aeneas and founded Rome in the year 3198.

The Early Formation of Rome

The city of Rome was first laid out in the shape of a quadrangle on the Palatine Hill, with the other six famous hills added later by successive kings. The initial walls of the city were low, and Romulus’ brother, Remus, mocked them by leaping over them. This act of defiance cost Remus his life; Romulus killed him in a fit of anger, thus becoming the sole founder of the city.

Romulus’ Leadership and the Early Romans

Romulus, now the first king of Rome, governed a community of outcasts and discontented young shepherds. These people were so despised by their neighbors that their daughters refused to marry them. For a time, it seemed as though the Roman experiment would fail before it truly began, lacking the population to sustain it. But Romulus, ever clever, devised a plan. He announced a great festival, knowing it would attract nearby Sabines. During the celebration, Romulus and his followers abducted the Sabine women, an act that sparked a war with the Sabine people. However, Rome’s courage and strategic genius led them to victory. Eventually, peace was brokered, and the Romans and Sabines united, growing stronger together.

The Growth of Rome

At this time, Rome’s territory was small—only about two miles in circumference. The population was proportionally small as well, but Romulus’ creation of an asylum for fugitives, criminals, and other outcasts helped swell its numbers. These newcomers brought with them the vices and customs of their native lands, creating a melting pot of cultures. Initially, this seemed like a wise strategy to increase Rome’s population, but Romulus soon realized that laws and order were needed to maintain control. Thus, he established a formal legal code and created the Senate, a council of 100 of the wealthiest and most respected citizens, to help govern.

These senators were called Patres (Fathers) or Senatores, and they were initially drawn from the wealthiest and most influential families, the Patricii. These elite families held the power to protect the poorer citizens, the Plebeii (Plebeians), who often had little say in the affairs of the state.

Romulus’ Disappearance and Legacy

Romulus’ reign ended mysteriously. During an assembly with the people, a storm suddenly arose, and Romulus vanished from sight, possibly taken up to the heavens. This disappearance was later interpreted by the Romans as his deification, with a man named Proculus claiming to have seen Romulus in the sky, now a god, ordering that he be honored as Rome’s protector.

However, some believe that Romulus was murdered by a group of discontented senators, either because they had suffered under his rule or saw his death as an opportunity to seize power. Regardless of how he died, Romulus’ legacy as the founder of Rome endured, and the city’s future leaders would build upon the foundations he laid.

The Reign of Numa Pompilius

Following Romulus’ mysterious disappearance, Numa Pompilius, a man renowned for his piety and wisdom, became the second king of Rome. Unlike Romulus, who was a warrior and founder, Numa was a deeply religious figure. His reign was marked by peace and a strong emphasis on religious and spiritual practices. Numa established many of Rome’s sacred rites and rituals, making sure that the gods were properly worshiped to ensure the prosperity of the new city.

Numa is credited with organizing the priesthoods of Rome, appointing priests and augurs to interpret signs from the gods. He also introduced the Vestal Virgins, dedicated to keeping the sacred fire burning continuously as a symbol of Rome’s eternal power. In addition, Numa introduced the concept of legal observance of religious festivals, grounding the city’s laws and customs in divine will. His rule was less about conquest and more about cultivating an orderly society, teaching the Romans a sense of moral duty and respect for the gods. Under his leadership, Rome began to take on a more civilized and refined character, with a focus on justice, piety, and moderation.

The Rise of Hostilius and Military Expansion

The third king of Rome, Tullus Hostilius, was a stark contrast to Numa. Whereas Numa had fostered peace and religious observance, Hostilius was a warrior king, eager to expand the Roman borders through military conquest. His reign brought Rome into conflict with neighboring tribes, most notably the Albans, a powerful city-state near Rome.

The famous story of the Horatii and Curiatii brothers occurred during Hostilius’ reign, a tale of sibling rivalry and valor. In a battle between the Romans and the Albans, three brothers from each side fought to determine the outcome of the war. The Romans, with their three Horatii brothers, eventually triumphed, despite the odds. The last remaining Horatius was able to defeat all three of the Curiatii brothers, ensuring Roman victory. The Albans were subsequently conquered, and their city was incorporated into the Roman state. Hostilius’ reign was characterized by military strength and a drive for expansion, establishing Rome as a formidable power in the region.

King Ancus Marcius: Building the City

Ancus Marcius, the fourth king of Rome, continued Hostilius’ expansionist policies but also focused on improving Rome’s infrastructure. He is credited with building the first bridge across the Tiber River, connecting the city more effectively to the surrounding regions. Ancus also fortified the city’s defenses and established new colonies to strengthen Rome’s presence in Italy. Under his leadership, Rome grew both in size and influence, becoming a more organized and connected society.

The Tyranny of Tarquin the Elder

The fifth king of Rome, Tarquinius Priscus, was an Etruscan, and his reign saw the influence of Etruscan culture on Rome’s political and military systems. Tarquin was a shrewd and ambitious leader who sought to strengthen Rome through both military campaigns and civic projects. His reign is particularly notable for the construction of the Circus Maximus, a massive chariot racing stadium, and the completion of Rome’s first sewer system, the Cloaca Maxima, which still exists today.

Tarquinius Priscus’ rule also saw the formalization of Roman military organization and the use of the Roman legion as a primary instrument of expansion. His reign marked a period of great prosperity for Rome, but it was also one of intrigue and political maneuvering. Tarquin was eventually assassinated, allegedly by a conspiracy of nobles who felt threatened by his growing power.

The Tyranny of Tarquin the Proud

Tarquinius Priscus was succeeded by his son, Tarquinius Superbus, known as Tarquin the Proud. Tarquin’s reign was marked by cruelty and excessive ambition. He ruled as a tyrant, disregarding the rights of the Senate and people, and resorting to violence and intimidation to maintain control. Under his rule, the Roman aristocracy suffered greatly, as Tarquin sought to centralize power in his own hands.

His downfall came with the infamous story of his son’s rape of Lucretia, a noblewoman who committed suicide after being violated. Her death sparked outrage and led to a revolt led by Lucius Junius Brutus and other Roman nobles. This revolt led to the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of the Roman Republic in 509 BCE. The fall of Tarquin the Proud marked the end of the Roman Kingdom and the beginning of the Republic, which would go on to shape the course of Roman history for centuries to come.

The Establishment of the Roman Republic

With the expulsion of Tarquin and the end of the monarchy, Rome became a republic. The Romans established a system of government that was based on elected officials, including consuls, who were elected annually to lead the city and its military. The Senate, composed of aristocratic leaders, became the governing body, advising the consuls and guiding the direction of the Republic. The creation of the Republic was a major turning point in Roman history, marking the shift from autocratic rule to a more participatory government, although power was still largely in the hands of the patricians, the elite class.

The early years of the Roman Republic were filled with challenges, including internal power struggles between the patricians and plebeians (the common people). Over time, however, the plebeians gained more political power, eventually leading to the creation of the office of the Tribune, which gave them a voice in the government. The Republic would go on to expand Rome’s borders through conquest, diplomacy, and alliances, laying the foundations for the eventual rise of the Roman Empire.

(12) Tarquinius Superbus was the seventh and final king of Rome—proud and cruel. Despite his tyrannical rule, he expanded Rome’s territory into several strong provinces of Italy, which the Romans later governed with more fairness and goodwill than he had shown in oppressing his neighbors. His name became infamous, especially after his son Tarquinius raped the virtuous Lucretia. This act of violence, along with the disgrace brought to her family, sparked a revolution, and the people deposed him, seeking a different form of government that would reflect more of Rome’s desire for freedom.

(13) This period of Rome’s monarchy lasted nearly 245 years since the city was first founded—a short time when compared to the histories of other great nations. Yet, for Rome, it was still her infancy. At this stage, Rome had only made a name for herself within her own region, not much further. But once she had freed herself from the oppression of her last king, she quickly extended her reach over Italy and began to make her presence known throughout the world. Power no longer lay in the hands of one king, but was now entrusted to two citizens who were elderly and wise, and of high rank, but they held the position more as trustees than sovereigns. The Romans took steps to avoid the arrogance of their last king. Their new leaders were called Consuls, from the word consulendo, meaning “to consult,” and their term in office was set to be annual—unlike the indefinite reign of the kings, which lasted until death. The symbols of their office, such as the twelve lictors and fasces, were shared between them, each consular pair taking turns each month. This system lasted for nearly six years, until the Romans, inspired by Greek governance, sent three esteemed citizens to Athens to study their laws and customs, which were highly regarded throughout the world as the foundation of learning.

(14) Upon their return, the Romans adopted their own written laws, which were first recorded on twelve bronze tablets. These laws, known as the Leges Duodecim Tabularum (The Twelve Tables), formed the basis of Roman legal system. The consuls’ power was reduced, and ten men, called the Decemviri (the Ten Men), were given almost as much power as the kings or consuls, though this was temporary. The Decemviri ruled for about three years, until Appius Claudius falsely claimed a woman named Virginia as his slave in order to dishonor her. Her father, in desperation, killed his daughter to protect her from further abuse, which enraged the people. They overthrew the Decemviri and restored power to the consuls. In time, the Tribunes of the Plebs were granted the same powers as consuls, though not the title itself, in a significant victory for the common people.

(15) Under this form of government, Rome continued to grow for another 300 years after the fall of Tarquinius. Yet Rome had not yet reached its peak; it was still in its youth compared to the maturity of a man. Some of Rome’s most famous moments during this period include the war with Porsenna, the creation of the dictatorship and the tribuneship, the trial of M. Coriolanus, and many victories and laws, including the Lex Agraria, Lex Publia, and Lex de Ambitu. Other notable events included the establishment of the censors, the conspiracy of the servants, and Rome’s eventual capture by the Gauls, though it was freed by the general Camillus. After more wars, such as the Punic Wars, Rome expanded, conquered, and built its power, laying the foundation for her future empire.

(16) By this time, Italy was under Roman control, and Rome’s power grew even further. Within 100 years, Rome had fought wars with Macedonia, Persia, Carthage, and Numantia, among others. Rome was unstoppable in its expansion and military success, and soon after, the wars with Mithridates and the Social War helped cement her dominance. Famous Romans such as Scylla, Cicero, Caesar, Pompey, and others shaped this era, marking the end of the Greek Empire and the beginning of the Roman Empire under Augustus Caesar, around 700 years after Rome was founded.

(17) Rome’s system of consuls continued until Julius Caesar returned from Spain, victorious over Pompey’s forces. The Senate, out of fear and respect for his power, granted him new titles such as Pater Patriae (Father of the Country) and Dictator Perpetuus (Dictator for Life), which Caesar solidified through his actions. He soon amassed power equal to or greater than what the Senate had originally given him. His assassination by Brutus and Cassius led to a brief period of rule by the Triumvirs—Octavian, Antony, and Lepidus. Ten years later, Octavian (now Augustus) became the sole ruler of the empire, and the title of Emperor was born, continuing in his successors to this day.

(18) Despite challenges and divisions, Rome continued to thrive. However, when the imperial capital was moved to Byzantium and the empire was divided into East and West under Theodosius, the Western Roman Empire began to crumble. Eventually, the title of Emperor was no longer held in Rome but in Germany, where the Holy Roman Empire was established, governed by various princes and bishops. The empire’s power was spread across Europe, with seven electors choosing the emperor, and various noble titles holding sway over different regions.

(19) Rome’s glory, at its peak, was remarkable. With a population spanning fifty miles and a location along the Tiber River, she was protected by towering city walls and had 37 gates. On the seven hills where Rome was founded—Palatine, Capitoline, Viminal, Aventine, Esquiline, Caelian, and Quirinal—stood the mighty city. The emperor Constantius, upon visiting, was struck by the vastness of the city’s monuments: temples, baths, theaters, triumphal arches, aqueducts, and more. He marveled at how nature had poured all her efforts into creating such a magnificent city. Yet, despite her grandeur, Rome could not sustain such glory forever, and, like a stretched string, it eventually snapped.

(20) Once divided, the Roman Empire became vulnerable to barbarian invasions. The Goths, Huns, Vandals, and others sacked Rome, and what remained of the empire became a mere shadow of its former self. The title of Emperor was transferred to Germany, where it continued under the Holy Roman Empire. Meanwhile, Rome’s political and spiritual power waned, and the once-great empire fell into history.

(31) As for the current state of the Roman Empire, I leave that to modern authors who have the space and knowledge to describe it in detail. My aim here was to briefly outline the rise, expansion, and decline of Rome’s ancient government.