Description

Introduction

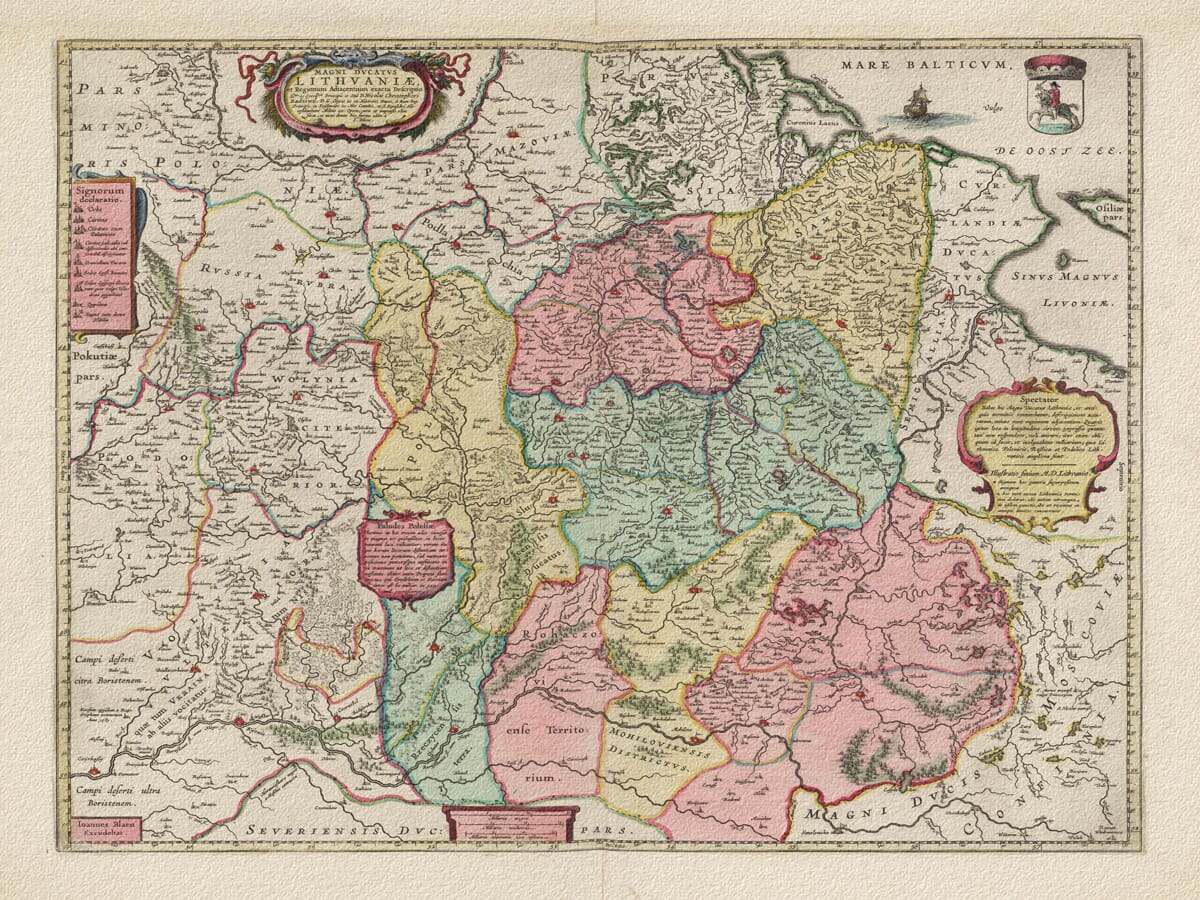

A beautifully reproduced map of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania offers a window into a bygone era when the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth dominated vast swathes of Eastern Europe. This fine reproduction, created by The Old Map Company of Great Britain, faithfully captures the richly coloured detail and ornate design of the original seventeenth-century cartographic masterpiece. The map’s content and aesthetics are steeped in historical significance: it reflects the political boundaries, territorial organization, and cultural geography of its time with remarkable clarity. At the same time, as a modern high-quality reproduction, it holds tremendous appeal for collectors and enthusiasts of historical cartography. The following analysis explores the historical importance of this map and discusses its value to collectors, highlighting its aesthetic qualities, expert craftsmanship, and educational significance.

Historical Context

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was, in its heyday, a principal partner in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795), one of the largest and most populous states in Europe during the early modern period. This Commonwealth was a bi-federal union of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and at its height it encompassed not only present-day Lithuania and Poland but also vast territories that today lie within Belarus, Ukraine, Latvia, and portions of Russia. A map of the Grand Duchy from that era captures this expansive realm at a time when its political influence and territorial reach were near their zenith. The reproduction map, based on an original engraved around the mid-1600s, freezes a moment in history when the Commonwealth’s borders were intact and its constituent lands were unified under a common governance.

Such a map is historically important because it documents the geopolitical reality of Eastern Europe in the seventeenth century. It delineates the boundaries of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in relation to its neighbours, offering insight into the political balance of power at the time. On the map, one can discern the frontiers of the Commonwealth abutting the domains of rival powers such as Tsarist Russia to the east and the Ottoman Empire’s vassal states to the south. By portraying the Grand Duchy’s territorial extent, the map serves as a visual record of national sovereignty and administrative authority. It likely also outlines internal divisions—such as provinces or palatinates (voivodeships)—hinting at how the sprawling Grand Duchy was organized and governed. In an era long before modern nation-states and accurate satellite mapping, such cartographic depictions were invaluable for understanding and managing large territories. Nobles and officials of the Commonwealth could use maps like this to grasp the scope of their lands, plan military campaigns, or negotiate treaties, making the original map a tool of statecraft as well as a work of art.

Equally telling are the cultural and historical details embedded in the cartography. This map was produced during a time when Latin was the lingua franca of scholars and mapmakers, so its text is likely in Latin, with places and regions labelled according to classical or contemporary Latinized names. This reflects the cultural milieu of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, where multiple languages and ethnicities coexisted—Lithuanian, Polish, Ruthenian (Belarusian/Ukrainian), Latin, Yiddish, and more—yet official documents often shared a common Latin vocabulary. The presence of Latin script and nomenclature on the map underscores how cartography served as a cultural bridge, translating a diverse landscape into a universally understood scholarly language. Furthermore, the map’s creation was a collaborative effort that spanned nations: the data and initial surveys for mapping the Grand Duchy were in part collected by local magnates (notably the Radziwiłł princes of Lithuania) and then handed to skilled Dutch engravers for production. This international collaboration highlights the era’s exchange of knowledge and the importance attributed to mapping distant regions. In essence, the historical context of this map encompasses not only the political configuration of Eastern Europe but also the intellectual and cultural currents that allowed such a map to come into being.

Value to Collectors and Enthusiasts

A 17th-century map of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (reproduction by The Old Map Company) illustrates the intricate detail and decorative artistry typical of the era. The map displays the vast expanse of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth with colour-outlined borders, detailed town markings, and elaborate cartouches.

The reproduced map is a shining example of Baroque-era cartography, where geographic information and artistic embellishment were woven together. In terms of geographic content, the map is extraordinarily detailed for its time. It charts a dense network of rivers snaking across the Grand Duchy and its adjoining regions—from the mighty Dnieper and Daugava down to smaller tributaries—since rivers were crucial for transport and delineating borders. Hundreds of cities, towns, and settlements are pinpointed and named, providing a comprehensive gazetteer of the region as it stood in the 1600s. Major cities of the Grand Duchy, such as Vilnius (Wilno) and Kaunas, appear prominently, as do other important urban centres of the Commonwealth like Kraków, Warsaw, and Lviv (identified by their contemporaneous names). By including locales stretching from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Black Sea steppes in the south, the map conveys the vast geographic scope of the Commonwealth. Political boundaries are drawn with coloured lines or shadings to distinguish the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from adjacent realms. For instance, one can observe the outline of Lithuania’s border merging with that of the Polish Crown to the west and delineating a frontier with Moscow’s dominions to the east. These boundary markings on the map are significant: they reflect how the Commonwealth’s domains were partitioned internally (Lithuania versus Poland proper) and externally how the state understood its extent vis-à-vis neighbouring powers. In an age without modern political maps, this was a definitive representation of sovereignty—effectively the Grand Duchy’s profile on paper.

Beyond raw geography, the map is rich in cultural geography and historical annotation. Early modern mapmakers often peppered their maps with textual notes and illustrations that tell stories about the land. On this Grand Duchy map, there are likely small inscriptions in Latin describing significant events or features. For example, in regions of today’s Ukraine that were part of the Commonwealth, the map includes notes on famous battles or the locations of important fortresses. Indeed, contemporary accounts of this map mention vignettes depicting battles near Smolensk and along the Dnieper—conflicts that would have been fresh in collective memory and pertinent to the map’s audience. These illustrated battle scenes and notes serve to remind viewers that this is not an abstract space but land over which wars were fought and history was made. The inclusion of such details transforms the map into a chronicle, preserving narratives of military and political history alongside topographical information. It reflects the seventeenth-century practice of viewing maps as multi-dimensional documents: tools for navigation and administration, but also canvases for celebrating triumphs, commemorating losses, and warning of perils.

Aesthetically, the map is a tour de force of cartographic artistry, and the reproduction preserves these artistic flourishes magnificently. In the age of the original map’s creation, mapmakers like Willem Blaeu—whose workshop published the source map in the 1640s—were renowned for their ornate decorative elements. This map features cartouches, which are Baroque decorative panels used to frame the title, legends, and other textual information. At the top or corners, one finds grand title cartouches embellished with heraldic crests and allegorical figures. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania’s map, for instance, bears the coat of arms of Lithuania (the iconic armoured knight on horseback, known as the Vytis) proudly within one such cartouche. It would not be unusual if the Polish White Eagle emblem is also present or paired with the Lithuanian knight, symbolizing the duality of the Commonwealth. These symbols anchor the map in the political reality of its time, effectively stamping authority and identity onto the landscape depicted. In the lower corners or edges, additional ornamental cartouches contain the scale of miles and explanatory text; the scale is artfully rendered as a drawn ruler or scroll, sometimes attended by cherubs or classical figures using a compass or callipers, signifying the measurement and precision that went into mapping. The reproduction preserves these fine details: one can admire how a tiny cherub’s face or a lion’s paw holding a shield is crisply defined, revealing the level of craftsmanship in the original engraving.

Moreover, the map’s wide margins and open seas provided space for imaginative artwork that delighted the viewer’s eye. In the Baltic Sea portion of the map, sailing ships with billowing sails are depicted riding the waves, harkening to the maritime trade on the Baltic and perhaps the importance of the port city of Gdańsk (Danzig) in that era. Among these ships lurks a fantastical sea monster – a common feature in maps of the time – which adds a touch of myth and warns of the mysteries that lay in uncharted waters. A lavish compass rose adorns the sea as well, with its starburst of colures and fleur-de-lis pointer indicating north; this not only serves a practical navigational purpose but also contributes to the map’s visual harmony. Every corner of the map is utilized, from images of Neptune or mermaids in the oceans to illustrations of mountain ranges and forests on land drawn in profile. These artistic embellishments reflect the worldview of the time: a blend of empirical observation and creative interpretation. The map was as much an art object meant to impress and educate as it was a navigational guide. In reproducing this map today, all these cartographic details — the bold outlines of provinces, the Latin annotations, the heraldic and mythical imagery — are rendered with stunning clarity. The result is a map that is not only geographically informative but also truly beautiful, capturing the imagination of anyone who beholds it. The cartographic significance of this piece, therefore, lies in its dual character: it is both a faithful record of the Grand Duchy’s 17th-century landscape and a masterful example of the mapmaker’s art that influenced how later generations would visualize Eastern Europe.

Cartographic Significance

Antique maps have long been treasured by collectors, and a reproduction of a map as significant as this one holds special appeal. For collectors and history enthusiasts alike, this map is far more than a simple print; it is a tangible connection to a pivotal period in European history. Owning the reproduction of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania map allows one to enjoy the same visual and intellectual feast that a seventeenth-century noble or scholar might have experienced when poring over the original. There is an undeniable allure in tracing the old borders and place-names with one’s finger and reflecting on how the world has changed since those lines were drawn. For those with personal or ancestral ties to Lithuania, Poland, Belarus, or Ukraine, the map carries a deeply sentimental resonance as well: it depicts the lands of their forebears at a time when these regions were united in one of Europe’s great kingdoms. As a collector’s item, the map represents a confluence of art and history, making it a showpiece that can spark conversations in a library, office, or living room. Unlike mass-produced posters or modern maps, a fine reproduction like this has a certain exclusivity and scholarly charm; it signals the owner’s appreciation for historical depth and classical aesthetics.

One of the key reasons collectors prize this reproduction is its aesthetic and material quality. The Old Map Company has reproduced the map with exceptional care, mirroring the craftsmanship of the original. Printed using state-of-the-art giclée techniques on heavy, textured archival paper, the reproduction mimics the look and feel of an antique map that might have been printed on hand-pressed rag paper centuries ago. The richly saturated colours on the map – from the green and yellow washes indicating different regions to the red and gold accents on cartouches – are faithfully replicated to match the hand-painted hues of authentic 17th-century maps. This attention to colour accuracy and detail ensures that the map’s decorative elements stand out: the delicate shading in a forested area, the vivid red of a noble’s coat of arms, or the subtle blue of a river’s course all appear as intended by the original cartographer. Collectors will notice that even the aging effects have been considered; the paper of the reproduction has an “aged” tone and a slight texture, so it does not look too starkly modern or glossy. Instead, it exudes the gentle warmth of a venerable document. Such details matter to aficionados of historical maps, who value authenticity. The craftsmanship involved in creating this reproduction means it can be proudly displayed as a piece of fine art. In fact, framed and matted, it could easily be mistaken for an original antique by the casual observer, which is a testament to the quality achieved.

Beyond its visual appeal, this map reproduction holds immense educational value, which further heightens its appeal to collectors who are often lifelong learners and historians at heart. Each element on the map can teach something: the old place-names and boundaries invite research into how those places are known today and why borders have shifted. A collector can spend hours comparing this map to a modern map of Eastern Europe, gaining insight into the dramatic territorial changes brought about by wars, partitions, and nation-building. For example, someone might note that areas labelled as “Polonia” (Poland) on this 17th-century map include cities that are now in Ukraine or Belarus, leading to a deeper exploration of the Partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the late 18th century. The map thus serves as a springboard into history, geography, and even genealogy. Teachers and lecturers also find such high-quality reproductions invaluable; hanging in a classroom or auditorium, the map can captivate students’ attention and make a lesson on European history or cartography tangible and engaging. The presence of Latin inscriptions and historical notes on the map allows educators to discuss how knowledge was recorded and shared in the past, as well as how historical maps can contain biases or propaganda (for instance, glorifying certain conquests or implying rightful ownership of contested lands). In a way, the map is a primary source document, and owning the reproduction is like having a museum piece at one’s fingertips, ready to be examined and interpreted.

For the discerning collector, there is also intrinsic value in the story of the map’s creation and the legacy of its cartographers. Knowing that this map originated from the famed Blaeu workshop in Amsterdam, a collector can appreciate it as part of the broader narrative of cartography’s Golden Age. The Blaeu family and their contemporaries revolutionized map-making, and this Grand Duchy of Lithuania map is one of their crowning achievements in regional mapping. Collectors often feel they are custodians of history; by acquiring a reproduction of this map, they are helping to preserve and disseminate the knowledge and beauty it contains. It’s a form of stewardship, ensuring that the map’s legacy endures even as original copies become rarer and are kept in controlled archives. Furthermore, reproductions like this democratize access to historical art. Not everyone can obtain an original XVII-century map (which would be exceedingly expensive and fragile), but a reproduction allows many to enjoy and study the map’s content. This broadens the community of enthusiasts and keeps interest in historical cartography alive. From a collector’s perspective, the value of the reproduction is not in monetary appreciation (as one might expect from an original antique) but in the lasting enjoyment and enrichment it provides. Each time one gazes at the fine details – be it the mythical creatures in the Baltic Sea or the delicate script marking a town – there is something new to discover or ponder.

In sum, the collector appeal of this Grand Duchy of Lithuania map reproduction is multifaceted. It lies in the map’s striking visual beauty, its precise and museum-quality craftsmanship, and the deep well of historical knowledge it holds. Owning it is like owning a slice of 17th-century history, rendered in exquisite detail. Whether one’s interest is primarily artistic, driven by heritage, or purely scholarly, the map satisfies on all counts. It is both a conversation-starting décor piece and a serious reference map that rewards careful study. For these reasons, collectors and appreciators of historical cartography find tremendous value in this reproduction, as it enriches their collections and their understanding of the world that was.

Conclusion

The reproduction map of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania exemplifies how a single artifact can encapsulate an era’s historical significance while providing timeless aesthetic pleasure. In the map’s finely drawn borders, we see the political contours of a powerful Commonwealth that has since vanished from the world’s maps, reminding us of the ever-shifting nature of nations. In its myriad place-names and annotations, we catch echoes of cultural and historical narratives that shaped Eastern Europe. And in its sumptuous cartouches, vibrant colors, and whimsical illustrations, we experience the artistry and craftsmanship of the Age of Exploration’s master cartographers. The Old Map Company’s reproduction has faithfully preserved all of these elements, allowing modern audiences to appreciate the map just as a seventeenth-century viewer might have – with wonder, curiosity, and admiration.

For collectors, scholars, and history enthusiasts, this map is more than a decorative image; it is a bridge across time. It transforms a wall into a portal to the past, sparking dialogue and discovery. The historical implications captured in the map educate and inspire, while the sheer beauty of its execution gratifies the senses. In an era when digital maps and GPS have become mundane, an ornate antique map (even in reproduction) reawakens our sense of exploration and respect for the knowledge of those who came before us. Ultimately, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania map reproduction stands as a testament to the enduring value of historical cartography. It highlights how the careful study and preservation of old maps can deepen our understanding of history’s landscape, and how owning such a reproduction can bring the past to life in our present-day spaces. Through this map, the legacy of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth continues to be celebrated and remembered, its story told in lines, symbols, and colours that have fascinated viewers for centuries and will continue to do so for generations to come.