Description

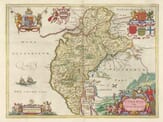

VERSO of John Speed’s Old Map of CUMBERLAND

Chapter 44 (Modern Translation)

(1) Cumberland, the most north-western county in England, borders southern Scotland. It’s separated from Scotland partly by the River Kirskon, then by the River Esk, continuing across the Solway Moss until it reaches the Solway Firth—called Itune Bay by the ancient geographer Ptolemy. To the northwest lies Northumberland; to the east is Westmorland; to the south, Lancashire; and to the west, it is entirely bordered by the Irish Sea.

(2) The county is long and narrow, pointing south like a wedge. That southern end is full of steep hills, which is why it’s known as Copeland (from “copped” or peaked land). The central area is flatter and more populated, providing enough resources to support human life. The northern part is wild and sparsely inhabited, also covered with hills like Copeland.

(3) The air is sharp and cold, and it would be even harsher if the tall hills didn’t block the northern storms and falling snow.

(4) Still, this county is rich and filled with a variety of resources. Though rugged, the hills are covered with sheep and cattle. The valleys provide ample grass and grain. The sea offers a great supply of fish, and the land is home to many birds. The rivers contain a type of mussel that produces pearls—especially at the mouth of the River Irt. Locals collect these mussels as they lie open and feed on the dew, then sell them to jewellers. While the locals make only a small profit, the jewellers gain much more. The most valuable resource, though, is copper from the royal mines—particularly around Keswick and Newlands. The area also yields graphite (known as black lead), which is so abundant that it is not highly valued, though it would be hard to live without it.

(5) The earliest known inhabitants of the area during Roman times were the Brigantes, according to Ptolemy, who were spread across modern-day Westmorland, Richmond, Durham, Yorkshire, and Lancashire. When the Saxons drove the Britons out of the better lands, the Britons retreated to the remote mountains. There, they resisted the Saxons’ attacks, and according to the historian Marianus, the area got its name “Cumber” from the Kumbri, or Britons. Later, when the Saxons lost power to the Danes, Cumberland was considered its own kingdom. According to the Westminster Chronicle, King Edmund, with the help of Leoline, Prince of South Wales, conquered Cumberland. After blinding the two sons of King Dunmail (the local ruler), Edmund gave the kingdom to Malcolm, King of Scotland. From then on, the Scottish kings’ eldest sons ruled the region. Later, King Stephen gave the area to the Scots in hopes of gaining their support during troubled times. However, King Henry II later reclaimed it, as reported by historian William of Newburgh, returning it to English control. Many skirmishes followed between England and Scotland over this land, the worst being the Battle of Solway Moss, where the Scottish nobles, discontented with their general Oliver Sinclair, abandoned the fight and surrendered to the English. This disgrace so deeply affected King James V of Scotland that he died soon afterward from grief.

(6) Many Roman relics remain in this county. As the frontier of Roman Britain, it was heavily fortified. Sections of Hadrian’s Wall, built by Emperor Severus, still exist. Another line of defense, built by Stilicho under Theodosius, ran from Workington to Elmsmouth along the coast to defend against Picts, Irish raiders, and Saxon pirates. Roman remains, including forts, altars, and inscriptions of commanders, can still be found at Hardknott Pass, Moresby, Old Carlisle, Papcastle, and other locations—some unearthed, others still buried.

(7) The main city in Cumberland is Carlisle, shown as an inset on this old map of Cumberland is attractively located between the Rivers Eden, Petteril, and Caldew. The Romans called it Luguvallum; Bede called it Luel; Ptolemy, Lencopibia; Ninnius, Caer-Lualid; we call it Carlisle. It was a thriving Roman city, but after their departure, it was ravaged by Scottish and Pictish raids. King Egfrid of Northumbria rebuilt its walls, but later the Danes destroyed it again. It lay in ruins for 200 years until King William Rufus rebuilt the castle and settled Flemish colonists there to guard against the Scots—though they were eventually moved to Wales. King Henry I, Rufus’s brother, later established an episcopal seat (a bishopric) in Carlisle. The city lies at 17 degrees and 2 minutes west longitude, and 55 degrees and 56 minutes north latitude.

(8) West of Carlisle, at Burgh by Sands, King Edward I died during his campaign against Scotland—an untimely and deeply mourned death.

(9) Near Salkeld, on the River Eden, stands a monument of 77 large stones, each about 10 feet tall, with one at the entrance 15 feet tall. It was likely raised as a trophy of victory. Locals call it Long Meg and Her Daughters.

(10) Since this county lay on the frontier, it had 25 castles for protection and was believed to be guarded by the prayers of monks and religious communities at Carlisle, Lanercost, Wetheral, Holme Cultram, Dacre, and St. Bees. These were all dissolved by King Henry VIII, and their lands absorbed by the Crown. Because Cumberland was exempt from paying taxes (subsidies), it wasn’t divided into hundreds for Parliament records like other counties. However, it still had 16 market towns, 58 parish churches, and many smaller chapels.