Description

First Impressions and Cartographic Character

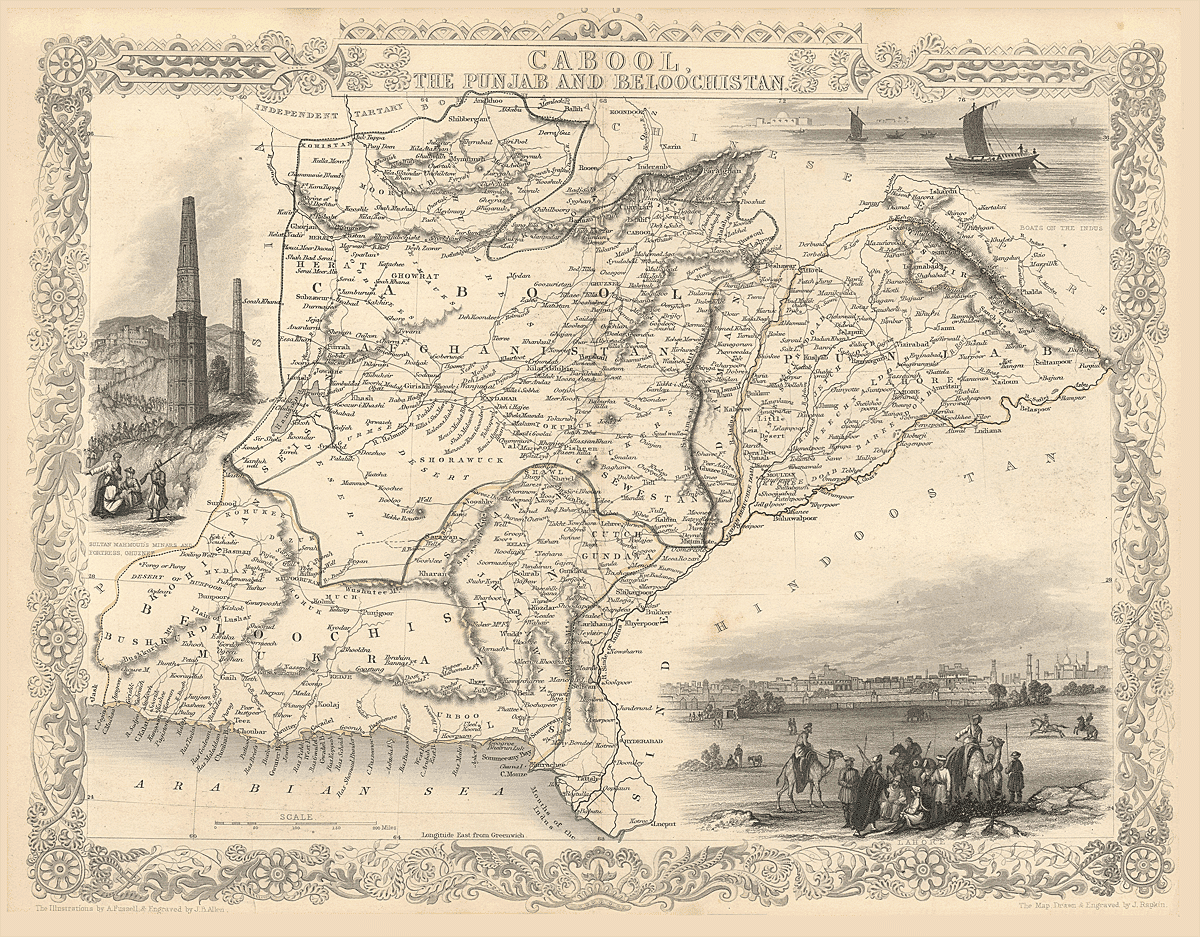

At first glance, this map announces itself as a product of mid-19th-century British cartographic ambition. Titled “Cabool, the Punjab and Beloochistan”, it presents not merely a geographical survey but a political vision of a region that sat at the hinge of empire. The map is framed by an ornate decorative border typical of Victorian atlas engraving, filled with scrollwork, floral motifs, and allegorical embellishments that elevate it from a utilitarian document into a work of art.

The engraving style is fine and confident. Mountain ranges are rendered in delicate shaded relief, rivers are carefully traced, and boundaries are hand-colored—green, yellow, pink, and blue—each hue quietly signaling administrative or political divisions rather than purely natural ones. The map is not crowded, yet it is dense with information: towns, caravan routes, deserts, rivers, tribal regions, and strategic passes all coexist in a carefully balanced composition.

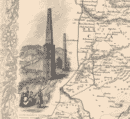

Inset illustrations—smokestacks and ruins to the left, boats on the Indus to the upper right, and a pastoral or caravan scene below—serve as visual footnotes, reminding the viewer that this land is at once ancient, commercial, and actively contested.

Publisher and Cartographic Lineage

This map was drawn and engraved by John Rapkin and published by John Tallis & Company, with illustrations credited to H. Warren and engraving by J. B. Allen. Tallis was one of the most prominent British map publishers of the 1840s and early 1850s, best known for producing the lavish Illustrated Atlas of the World. His maps combined geographical precision with decorative flair, targeting an educated middle-class audience eager to understand—and admire—the expanding reach of Britain.

Rapkin, Tallis’s principal cartographer, was admired for his clarity and elegance. His maps often synthesized the best available geographic intelligence with a distinctly imperial worldview. This particular sheet dates to circa 1851, a moment when British interest in Afghanistan and the Indus region was at its height following the First Anglo-Afghan War (1839–1842) and the annexation of the Punjab (1849).

Thus, the map is not neutral. It is an artifact of surveillance, consolidation, and curiosity—one that reflects British strategic anxieties about Russia, Central Asia, and the security of India’s north-western frontier.

Geographic Scope and Structure

The map spans a vast and varied territory:

-

Afghanistan (Cabool) at the center and north

-

The Punjab to the east

-

Sindh and the Indus Delta to the southeast

-

Beloochistan (Baluchistan) to the southwest

-

Portions of Persia (Iran) to the west

-

The Arabian Sea at the southern edge

The geography is structured around natural systems rather than political capitals. Mountain chains dominate the visual field, especially the Hindu Kush, Sulaiman Mountains, and the rugged highlands of Baluchistan. Rivers—above all the Indus and its tributaries—serve as organizing arteries for settlement and movement.

The map’s orientation subtly emphasizes routes: passes through mountains, river corridors, and caravan paths linking Central Asia to India. This is geography understood through mobility and strategy.

Afghanistan (Cabool): Mountains, Passes, and Cities

At the heart of the map lies Cabool (Kabul), clearly marked and centrally positioned. Kabul is shown not as an isolated capital but as a node in a web of routes leading to Ghazni, Jalalabad, Bamian, and Kandahar. These towns were of immense strategic importance to British planners, as control of them meant access through Afghanistan’s otherwise forbidding terrain.

The Khyber Pass, though not always explicitly labeled as such, is unmistakable in the eastern mountain corridors connecting Kabul to Peshawar. This pass had already become legendary in British military consciousness by 1851, synonymous with both invasion and disaster after the retreat from Kabul in 1842.

Other notable Afghan towns include:

-

Ghazni, remembered for its fortress and for British sieges

-

Kandahar, anchoring southern Afghanistan and linking it to Baluchistan

-

Herat, near the western edge, often called the “Key of India” in British geopolitical thought due to its proximity to Persia and Central Asia

The map emphasizes Afghanistan’s fragmentation: valleys, tribal regions, and difficult terrain dominate. It visually explains why Afghanistan resisted external control and why imperial powers viewed it as both a buffer and a battleground.

The Punjab: Rivers and Newly Annexed Power

To the east, the Punjab appears as a striking contrast. Where Afghanistan is mountainous and broken, the Punjab is structured, fertile, and river-defined. The five rivers—the Indus tributaries of the Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej—are clearly delineated, flowing in broad, confident strokes.

Major towns and cities stand out:

-

Lahore, prominently marked, newly transformed from Sikh imperial capital to British administrative center

-

Amritsar, religious heart of Sikhism

-

Multan, a historic fortress city on the Chenab

-

Peshawar, at the edge of the frontier, bridging Punjab and Afghanistan

-

Delhi, just beyond the main Punjab focus but visible as a reminder of imperial gravity

The Punjab had been annexed only two years earlier, in 1849, after the defeat of the Sikh Empire. This map reflects that transition: boundaries are clean, rivers orderly, and settlements dense. It is a land that appears governable, taxable, and agriculturally productive—qualities prized by colonial administrators.

Sindh and the Indus: Commerce and Control

Flowing southward, the Indus River becomes the map’s dominant axis. The river is shown as navigable, with inset illustrations of boats on the Indus, reinforcing its role as a commercial highway. British control of Sindh, achieved in 1843, had opened the Indus to steam navigation, a revolutionary development in colonial logistics.

Key towns include:

-

Hyderabad (Sindh)

-

Shikarpur, a vital trading hub

-

Thatta, once a great medieval port

-

Kurrachee (Karachi), emerging as a strategic harbor on the Arabian Sea

The Indus Delta is carefully mapped, its channels spreading like veins into the sea. This is imperial cartography at work: rivers are not merely natural features but instruments of power and movement.

Beloochistan: The Periphery of Empire

To the southwest lies Beloochistan, depicted as vast, sparsely settled, and harsh. Towns such as:

-

Kelat (Kalat), capital of the Khanate of Kalat

-

Quetta, still small but later to become a major British garrison

-

Gwadar, on the coast

are isolated points in a landscape dominated by deserts and mountains.

The map reflects British uncertainty here. Boundaries are looser, settlements fewer, and much of the interior remains vaguely defined. Beluchistan was not yet fully controlled but was increasingly important as a corridor between India, Persia, and the Arabian Sea.

Decorative Insets and Symbolic Meaning

The inset illustrations deserve special attention. The industrial ruins or smokestacks to the left may symbolize antiquity and progress in uneasy juxtaposition. The caravan scene at the bottom right evokes timeless movement across the land—traders, nomads, and soldiers alike. Together, these images suggest a region suspended between ancient civilizations and modern imperial transformation.

They also soften the map’s strategic hardness, inviting admiration rather than anxiety.

Historical Context at the Time of Publication

This map was published at a moment of deep imperial reflection. The First Anglo-Afghan War had ended in humiliation less than a decade earlier. British India had expanded dramatically, but not without cost. The Punjab was newly conquered; Sindh newly integrated; Afghanistan newly feared and newly studied.

The so-called “Great Game” between Britain and Russia loomed over every detail. Maps like this were tools of understanding and reassurance—ways to make sense of a vast, complex frontier by rendering it legible on paper.

Every town name, every river, every mountain pass reflects intelligence gathered at great expense, often through exploration, diplomacy, and war.

Closing Reflections

To study this map is to witness the meeting of art, ambition, and anxiety. It is beautiful, meticulous, and quietly assertive. It presents a region of immense cultural depth and geographical challenge through the lens of Victorian confidence, even as history would soon test that confidence again.

One can admire the precision of Rapkin’s engraving, the elegance of Tallis’s presentation, and the sheer audacity of attempting to capture such a landscape on a single sheet. Yet one also senses the tension beneath the surface—a land mapped not because it was known, but because it needed to be known.

This map is not merely a picture of Afghanistan, the Punjab, and Beloochistan. It is a portrait of empire at its thoughtful, cautious peak—measuring the world even as the world resisted being measured.